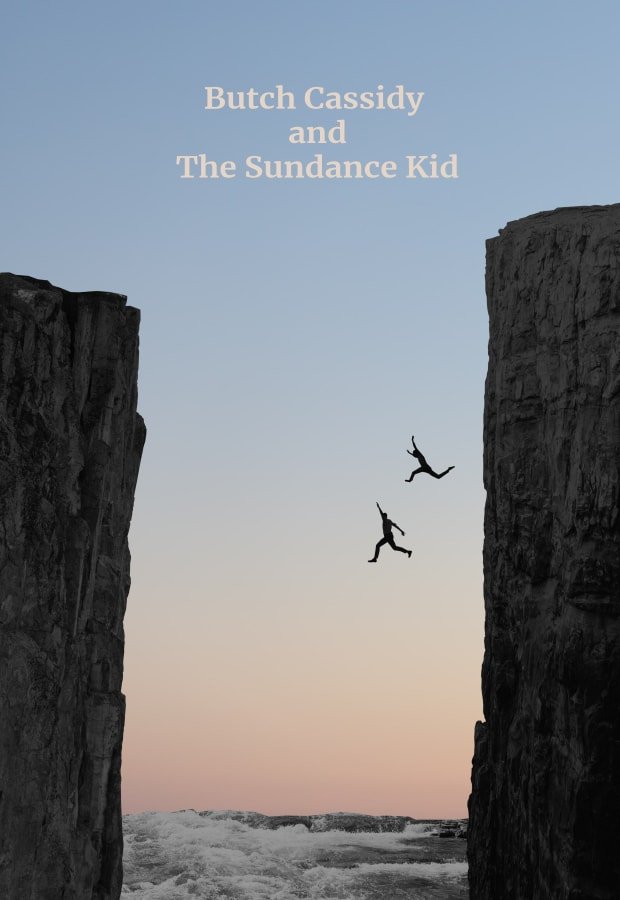

A story of two infamous outlaws who are forever entombed with the handsome young faces of Paul Newman and Robert Redford, who respectively provide the likable characters of Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid. The two fulfilling more than a lifetime of exploits, adventure and daring robberies, all the while having a hell of a lot of fun.

Be invited into a bromance to end all bromances as the pair go from robbery to robbery, and with it they seem to be chasing death. The thrill of the crime being the addiction, the money secondary. A western adventure, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid glorifies the criminal duo turning their history into a story of friendship and one more akin to that of brothers, than the real-life criminals they were – but still, you can’t help but root for them to get away, because they’re smart, quick-witted, loveable and the banter is just bloody brilliant.

The quick-to-laugh dialogue is further increased with physical humour that’s similar in style to Charlie Chaplin’s work; with explosions that are too close, a dangerous dance with a bull, and bicycle charades. Not only did the actors perform many of their stunts, they also thoroughly enjoyed doing them and got on incredibly well with each other, with Paul Newman stating it was the most fun he ever had filming. The enjoyment of filming and off-screen friendship lending a real credibility of brotherly love, as well as the respect that Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid are portrayed as having for each other. A scene that sums up this humorous and very loyal friendship is when Butch is challenged within his group for leadership, and though he reluctantly agrees to the fight, he whispers to the Sundance Kid “Listen, I don’t mean to be a sore loser, but err when it’s done, if I’m dead, kill him,” to which Sundance replies “Love to”.

Opening with an old sepia film, the story tells of a time our fated duo ran the West, the rhythmic clicking of the film’s projector further highlighting its centuries-ago past and instilling a romantic sense of nostalgia. Inserted between this are the words “most of what follows is true,” and events in the film are similar to what’s recorded – though the ending for one of them may differ, depending on what side of history you favour. But we’re not here for that, we’re here for the exceptional dialogue and picture postcard imagery of America’s outback, the cinematographer emulating the grandness of master photographer Ansel Adams, while keeping its colour. A particularly novel transition in the movie is when the filming moves from the projector and into the film reel itself, and with it transporting the audience back in time to the “real-life” Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, but with the opening scene keeping the sepia tones and the deathly stillness of a silent movie. But this is real-life now, not movie clips, and so the sound of everyday life is slowly added; occasional footsteps, the closure signs at bank tills, until it builds to the harsh and thunderous turns of locks and bolts, as the bank shuts its safe from prying hands – from their hands. Colour meanwhile is only added when the two outlaws are riding off into the sunset to begin their adventure over the rocky ridges and into the bright sunshine of daylight; the light of which diffuses into the sepia tones and to the introduction of colour that turns brighter and brighter, until the scenic scenes of nature verge on over-saturation. The director, George Roy Hill, later returns to using this same trick in the movie but with photographic stills; each sepia image layered over the one before and thereby creating a time jump for the characters. This jarring entry reminding the viewers that the character’s stories have been and gone, and that we’re just getting a glimpse of their past. This midway point of inserting modern-made-to-look-old-photographs isn’t done as smoothly as the film projector, but the photographs are more interesting now that you’ve come to know the characters, while revealing more of the relationships.

The manipulation of the film’s colouring is only one way Hill has added to the story, another is in its music – its catchy tunes befitting the movie’s release date of the 60s, while acting in defiance to the age difference and tone of the film. It shouldn’t therefore work. It really shouldn’t, but because the music is so sparingly used – when it does come into effect it emphasises the characters’ emotions; the romance/wooing, friendships, and fun – and when the music drastically cuts-off it tells of a change in fortunes.

The story begins and ends with the points of friendship and of their deep understanding of each other; the Sundance Kid is silent, direct, and aggressive when his self-held principles are challenged, while Butch Cassidy is talkative, charming, avoids violence and is ambitious in his planning. Together they rob trains, and spend time hanging out with the Sundance Kid’s girlfriend – who you get an inkling Butch likes. Although there’s no outward entanglement of a love triangle, which makes a nice change, leaving the audience to just enjoy the personalities on show.

From multiple train robberies, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid soon become men with too large a target on them – the chase scenes well played, and give a great sense of desperation – with little to no choice on the outcome. I won’t say if they get away or not, you’ll have to see for yourself.

Director: George Roy Hill

Other notable works:

- Slap Shot 1977

- The Sting 1975

Writer: William Goldman

Other notable works:

- Maverick 1994

- Chaplin 1992

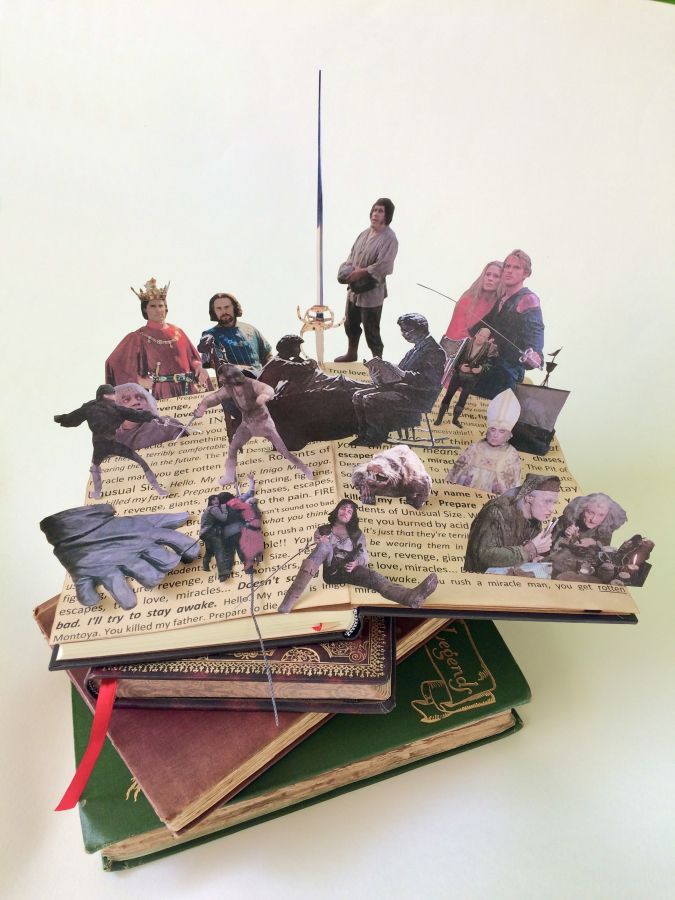

- The Princess Bride 1987

- Marathon Man 1976

- All The President’s Men 1976