Finger-painting has never achieved the likes of this before, Iris Scott’s work literally displaying the marks of the artist. Slightly, impressionist in style the paintings take inspirations from scenes in reality, although they are at times heightened to touch upon fantasy elements: Stormy Splendor Dragon Ember (2018), which feels like Scott’s way of seeing the world. In fact, she first saw this dragon when looking up at the sky in happiness and seeing his form within the clouds, to then later seeing him again in the brushstrokes of an abstract painting. Throughout all of Scott’s art there’s this contagiousness of joy; from dogs shaking the rain off their coats; with its splashes of water caught perfectly in a swirl of droplets, to then days full of sunshine, and the portrayal of wild animals. The personalities of these animals being shown; from closeups of highly realistic eyes; foxes that are jumping upwards at the fall of autumnal leaves; to scenes with polar bears roaring at the moon, that will make you think instantly of Philip Pullman’s writings. These creatures are alive, full of souls and equal to humans – a message the artist is keen to convey.

Much of Iris Scott’s work focuses on nature; animals proudly shown in their natural habitats; wild landscapes that reflect the bright sunshine or a sense of changing seasons: After the Snow Fell (2016), the barren tree trunks of winter replaced with a vibrancy of summer foliage, while in between snow lays all around them – the two patterns of summer and winter overlapping – displaying the power and life of nature.

Iris Scott also creates waterscapes that instantly relax you, and yet there is a separation within them: Green River Sockeye (2016) with the world below to the life above, with raindrops from the latter altering the water’s surface and distorting the view of what lies beneath, the image inviting you to see both perspectives while evoking a sense of mystery. Scott extends this effect of two views through the weather altering scenes of her urban-scapes: Mini Cooper Oncoming, the viewer’s perspective is rippled as though they’re looking through glass, behind which they’re safe and secure from the elements, while the city itself is transformed by nature as it meets the urban world; the lights from the cars bouncing off the wet tarmacked streets, while in other pictures umbrellas are held tight as the wind pulls against them. This relationship between humanity and nature is investigated again in I of the Needle (2019) with the Iris Scott shown to be stitching her dress as she stands on a carpet of “grass”, while the light switch behind her reveals it not to be a setting within nature, but a room, the highly decorated forest its wallpaper, and on closer inspection there’s a sense that the Scott’s dress is blending into the “forested” backdrop, either through a desire to become a part of it, or like everything else, its faux-nature. In actuality, the dress was a part of the painting in more ways the one, the real-life dress being a finger painted design by Scott, a sort of transference of image to reality.

I of the Needle, 2019, Oil Finger Painting with Brush-Painted Skin. Iris Scott.

I of the Needle, 2019, Oil Finger Painting with Brush-Painted Skin. Iris Scott.

Continuing to celebrate and embrace the beauty of nature, Iris Scott’s palette is predominantly hues of natural green, blue and yellow which are only slightly enhanced and with the occasional overlap of a vibrancy similar to the aurora borealis. Most of Scott’s scenes have a strong grounding of reality, while some have combined with an interlacing of abstract geometric patterns: Coyotyl (2018), which conjures the sense of a quilt sewn into the skyline. Scott also encompasses elements of mysticism within her landscapes: Exodus of Pisces (2019), and in the powerful women Scott portrays in her series of work on people: Sofia Returns (2018) and Fuchsia Shamanka (2019).

All of Iris Scott’s art is created by the use of her fingers, her hands protected by surgical gloves, but the dashes are still the thin lines of her fingers and nails. But how did she come to discover this way of working? It was all because Scott ran out of clean brushes to use, their bristles being covered in darker colours than she wanted to use, and with the painting needing just the smallest of touches, she used her fingers, and from there she discovered a new way of working; producing art that’s both impressionist and distinct, her images leading a new way to see and capture the world.

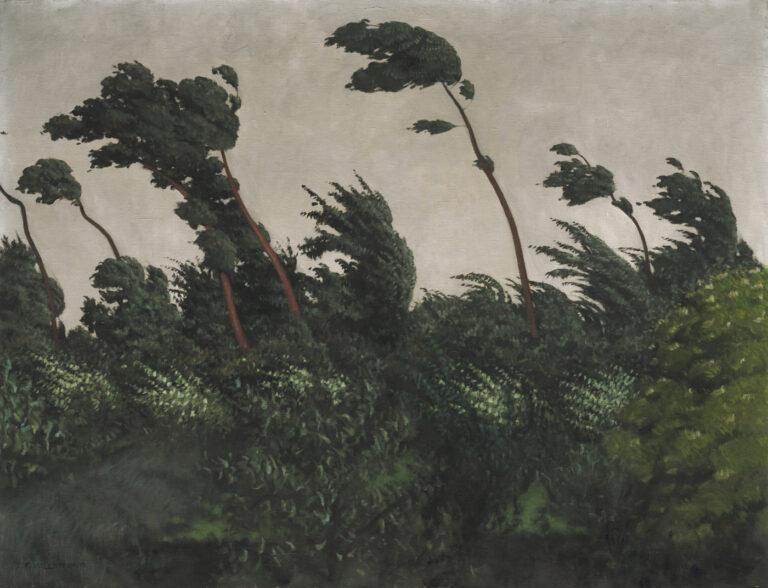

Coyotyl, 2018, Oil Finger Painting Plus Brushes. Iris Scott.

Coyotyl, 2018, Oil Finger Painting Plus Brushes. Iris Scott.

Iris Scott identifies her work and approach as instinctualism, a term coined by the artist to mean a return to the instincts of aesthetically beautiful and colourful artwork, the imagery of which can be seen in the natural world of fauna and flora. And once you’ve seen Iris Scott’s paintings there’s no way you can argue otherwise.