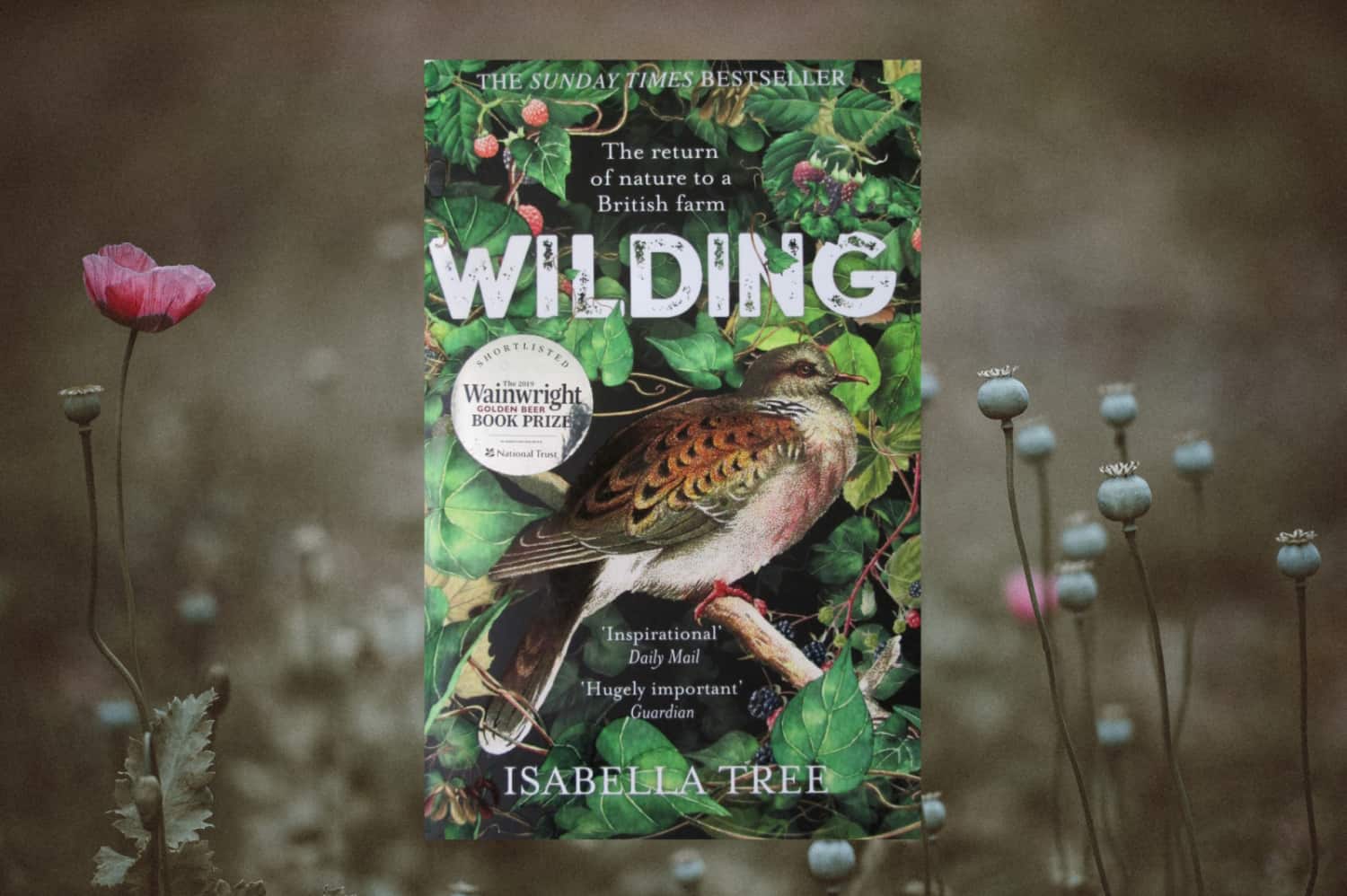

Wilding tells of a farm, Knepp estate, as it moves from the intensive farming of 3,500 acres and its controlled methods, in favour of passing it back to nature and leaving wildlife to once again take charge – that is, with a little help. Being early pioneers of such a scheme the gamble was high, filled with complaints and soaring with judgements that threatened to fly higher than the turtle-doves now returning to its vibrant land of yellow, with the over-exaggerated villain (cast by Knepp’s neighbours) played by the plant ‘ragwort’.

Following the journey of Knepp’s transformation by the owners – husband and wife, Charlie Burrell and Isabella Tree – the book is written in an easy to digest format of the first-person perspective of Tree (who’s an excellent narrator). The book covers not just their time of ‘rewilding’ – a seemingly applicable word that is none the less contentious as was/is the project undertaken at Knepp – but delves into; the history of agriculture (e.g. WW2, humorous folktales and royal hunting parties); firmly held beliefs of our modern viewpoints (even when faced with a recorded history of biodiversity that would beg to differ); to a breakdown of ecology including the microcosms of plants – that fascinatingly hold a partnership of warning systems to help ‘…ailing individuals or vulnerable offspring.’

Primarily however, Wilding explores the difficulties and challenges faced by the project of re-naturing (I fear any retribution of saying rewilding twice) and the vast rewards seen across the chains of biodiversity, minus large predators such as wolves and bears, though I expect (and hope) this is to follow in future books.

Divided by tasks, their obstacles, and surprises, rather than a chronological ordering of time (though there’s a helpful timeline at the start, and a structure of it within the chapters), the book sets to explore the land and it’s possibilities. In addition to which there’s an investigation of the land’s history – from ancient free-roaming species, to modern inventions such as fertilizers (which by the way are a by-product of weaponry), and hot points of discussion within the natural scientific community; such as the true history of closed-canopy forests – which certainly opened my eyes to wider possibilities.

‘We assume we know what is good for a species but we forget that our landscape is so changed, so desperately impoverished, we may be recording a species not in its preferred habitat at all, but at the very limit of its range.’

Wilding calls, hoots, and with the turtle doves’ turr–turr, shouts for a review of preconceptions, its example helping to lead a wider discussion on how we see and try to place nature, rather than letting it decide its own course – seen in a canal being allowed to return to its former state as a river.

The romantic cover of Wilding may bring you to open its pages, but it’s the poetic writing (such as the charming comparisons to Burrell’s childhood in Africa) that keep you captivated, whilst being engrossed by the dramatic stakes at risk. Feeling at times like a crime-noir merged with scientific papers and journals – there’s even a reference section at the back. The heroes of the story being Knepp estate and their colourfully characteristic advisors (pictured so easily in their bounding pursuits from strict boarding schools, to the wilds of nature), against the villains of misinformation and closed-off-minds. The in-depth research and evidence slowly challenging old theories, whilst showing proof is in the pudding with Knepp estate. An accompaniment of photographs illustrate the changes to the estate, and of the highlighted species returning to the land. There’s often a temptation in including photographs in a book to skip ahead and sneak more than a peek at them, but as you progress through Wilding and you become more in awe of Knepp you’ll find yourself repeatedly returning to look at the pictures with a new perspective. Another layer of enjoyment to the book are the quotes, poems and extracts of literature that come as a foreword to each of the chapters, and show a respecting of nature.

Tree avoids being dry in her recording of the past, and in the numerous facts she shares – because they’re so damn interesting, and with their being so many I happily jammed my friends inboxes with seventy-two messages filled with them, until they blocked me that is. But with species called beefsteak fungus, and facts from wild boars can “jump six feet and reach a speed of 30mph”, and blind spineless creatures can move twenty tons of soil, to a peacock and its special “relationship” to a BMW. I was really left with only one option – to ring my friends and sing about it instead.

Despite all my excitement at the book, there were perhaps too many listings of species or items, such as a good deal about farm equipment – however this was often curtailed at just the right point of reaching your limit. There’s also on occasion a temptation by Tree to veer away from the original point identified, and to delve instead to further arguments of importance, which can mean that after a few pages you lose your original footing. But this is easily forgiven and forgotten by the large provision of details, and successes by Knepp. For example, the highly successful increase in species (e.g. 62 bee species being found at Knepp in 2016) to a return of creatures that are at risk/endangered (e.g. nightingales, purple emperor butterflies and turtle-doves). The achievements of Knepp are just astounding and delightfully keep growing, while at the same time Tree creates the accurate and hard to deny facts of the species’ decimation as a whole, and the persistent threat still of their extinction. This book is not without its warnings.

Tree and Burrell experience many difficult situations in their return to nature, from fencing, funding, the inundating complaints of neighbours, approval of species, acclimatising, domesticated vs wild grazing animals, disrupted polo matches with attention seeking ponies, and the occasional onion bhaji pig thieves. To truly heart-breaking difficulties such as; the balancing of animals in sustaining the land; and the mis-use and underappreciation of Knepp by certain individuals, who like to play ‘cowboys’ or take pot-shots at the animals; to the discussion of society’s distancing with nature, especially in how new generations experience their relationship with wildlife.

There’s a cycle within the book with it starting and ending on the same point of nature’s capabilities, but throughout Wilding – which I sense will have a follow-up – the process has been expanded in possibilities, and not just in the estate of Knepp, but in the minds of the readers through generating knowledge, hope and an ambition of change, especially in a time where environmental news is predominantly negative.

Book Edition Information:

Publisher: Picador

ISBN: 978-1-5098-0510-5

Cover Design: Neil Lang, Picador Art Department

Presented Edition: 2019 Paperback

Background image courtesy of Annie Spratt on Unsplash