You’d be hard pressed not to have noticed how many songs have a structure of rhymes to them, but this doesn’t necessarily make them poetry, but neither are songs without rhymes or a melody not a poem. In the end the argument of whether poetry is songwriting or vice-versa, is just like the long complex relationships you often hear on the radio; both full of judgement or praise, that’s either for or against it. The only thing that matters here is that poetry can help provide new directions and styles of songwriting, which is great when you’ve hit that brick wall. With this in mind let’s look at some of the different forms of poetry, get fresh inspiration and maybe find yourself with the latest viral sensation and chart hit.

Sonnet

The term sonnet comes from the Italian word “sonetto” meaning little song or sound, which seems very apt here.

The structure of a sonnet is 14 lines, with each having 10 syllables. These syllables switch from being stressed to unstressed. Think of stressed as being emphasised, and a quieter syllable being unstressed. Meanwhile its overriding theme is about having a question, to then providing the answer to it e.g. “Why does it always rain on me? Is it because I lied when I was seventeen?” (Travis from ‘Why Does It Always Rain On Me?’) This song however isn’t a sonnet but it gives you an idea about the structure of a question to an answer.

The fourteen lines of a sonnet can also be broken down into four parts (also known as quatrains), this is typical of Shakespearean sonnets. The first part is the subject of the sonnet, the second more in depth information, and the third coming to a conclusion. Each part being four lines. The fourth part is the solution/answer and is two lines.

Does it rhyme? That’s totally up to you, while sonnets used to follow strict rhyming patterns (there’s a variety to choose from), more recently they haven’t rhymed at all.

Haiku

It might seem odd to include a poem that’s only three lines long, but with this restriction, you’re forced to come up with a way to tell a story and briefly convey an emotion that’s full of intensity. It’s really no surprise then that a book has been produced condensing Bob Dylan’s songs into haikus – his songs already being charged with stories that are full of the experiences of life.

The guiding structure of a haiku is 5 syllables first line, 7 syllables second and 5 syllables for the last one. You can always use the structure of a haiku for the song’s verse or even the chorus.

Usually haikus don’t rhyme, and break the flow of the rhythm so as to contrast its aspects or to conjure sharp images. Their themes are often on nature, with a word or description hinting at a season within the poem.

Image is courtesy of Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

Acrostic

Ever heard the rumour that if you play a song backwards, you can hear a hidden message? Or leave an album to run blank for a number of minutes and a secret track is revealed. Well, acrostic poems play within this as well, with certain letters of the words spelling out a hidden line/meaning/phrase or word. Typically, acrostic poems use the first letter of each new line to spell out its hidden secret. But you can also use the first letter of each word, or other word/sentence etc.

In this example, the song F.E.A.R. by Ian Brown has an acoustic structure with each letter of the word spelling out ‘FEAR’;

“For each a road

For everyman a religion

Find everybody and rule

Fuck everything and rumble

Forget everything and remember

For everything a reason

Forgive everybody and remember”

While he also later changed the structure;

“Fantastic expectations

Amazing revelations

Final execution and resurrection

Free expression as revolution

Finding everything and realising”

The easiest way to write an acrostic is to first decide your hidden word/phrase, and where you want this placed within the song. For example; the last letter at the end of each line; at the beginning of each word; or maybe a double acoustic – use the first and last letters; or even somewhere in the middle. To make your acrostic harder to spot, you could do something like; every second letter, in every second word, on every other line.

To make it more impactful have the hidden word(s) relate to the theme of the song. Finally, having chosen your acrostic, start building the lyrics around it.

Ode

Fittingly these old poems – which can be traced back to Ancient Greece – were often performed to the beat of music. In fact, an ode was rarely written and was predominantly sang instead. Meanwhile its subject matter is often of praise to something; person, object, experience, event etc, and exploring feelings and emotions within this.

When writing an ode try to think of something you’re deeply moved by/have intense feelings about. The stronger the emotions, the better the ode, as you can really get to the heart of what you’re singing about e.g. a person, experience etc.

In terms of structure, it’s usually between 3-5 stanzas (verses), the length of which is personal choice. As mentioned, odes usually have a melody to them; whether it’s a particular beat, rhyme, meter, or rhythm. How you go about it is your choice, but try to make sure there is a tune to it, and the clearer it is, the better the song.

Another point worth knowing about odes is that there are three different types. Pindaric; which is three verses, the first two of which have the same structure, while the third is different and provides a conclusion to the subject. Horatian, which has more flexibility, in that you decide the structure, but then all the verses have to follow this pattern. And then lastly there’s the irregular odes, which as you’ve probably guessed, follow no set rules.

Elegy

This poem is written in reference to someone who’s died – often mourning and holding them in great revere. In modern forms there’s no set rhyme or beat to follow in writing an elegy, only that it transitions from loss and grief, to consolation.

Elton John’s ‘Candle in the Wind’ is often said to be an example of an elegy – paying tribute to none other than Marilyn Monroe aka Norma Jeane.

“Goodbye, Norma Jeane

Though I never knew you at all

You had the grace to hold yourself

While those around you crawled

Goodbye, Norma Jeane

From the young man in the 22nd row

Who sees you as something more than sexual

More than just our Marilyn Monroe”

Ballad

Storytelling is the best way to think of a ballad; its forms being that of a narrative, and with the intention that it’s performed to music. Although, and this might seem like a large contradiction, it doesn’t always have to tell a story – though most do – as long as it’s emotionally charged. Still, when it’s intended to tell a story it does so from start to end, or as a scene set within it.

The intention of the ballad’s subject is to have a connection form to the wider audience e.g. a tragic love story. As such think about what experiences in your life would connect a stranger, partner, sibling, parent, friend etc together. Is it the joy of a first kiss? The pain of losing someone? The pressure of your first steps as an adult? Or seeing the world and fighting against it. Maybe even the news or pop culture etc.

The format of a ballad means it usually rhymes and is melodious; with sections of each verse rhyming together. For example, the end of the first and third lines, second and fourth/or just one pairing. A ballad can also have a repeating line placed at the end of each verse to really make an impact. Choose this line to poignantly point out the story’s motto, meaning etc.

Image is courtesy of Lee Campbell on Unsplash

End Rhymes

You can probably guess from the name, that end rhymes are when the last word in two or more lines (from a verse) rhyme together. However, the rhymes don’t have to follow directly after one another.

“Take me to church

I’ll worship like a dog at the shrine of your lies

I’ll tell you my sins and you can sharpen your knife

Offer me that deathless death

Good God, let me give you my life”

– Hozier, ‘Take Me to Church’

“Now ain’t nobody tell us it was fair

No love from my daddy cause the coward wasn’t there

He passed away and I didn’t cry, cause my anger

Wouldn’t let me feel for a stranger

They say I’m wrong and I’m heartless, but all along

I was looking for a father he was gone”

– 2Pac (Tupac Shakur), ‘Dear Mama’

End rhymes have the benefit of creating a natural rhythm. This, combined with the flexibility that it’s theme can be on anything, means that it’s commonly seen within music.

Villanelle

One of the more structured poems, the villanelle has a musical rhythm to it, whilst also being harder to construct. Although having said that, a lot of its lines get repeated – so you really need to make sure you’re happy with them.

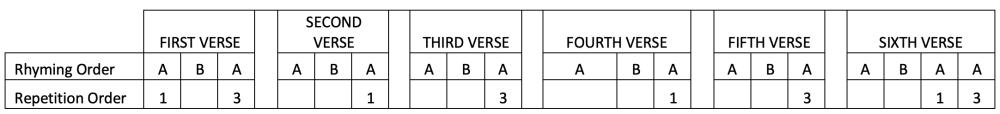

To begin with, a villanelle is made of 19 lines, and six verses. The first five verses are three lines each, while the final verse has four lines.

It’s rhyming scheme is that the first and last line of each verse (including the bottom two lines for the final verse) all rhyme together, as do the middle lines of each verse. For example: ABA/ABA/ABA/ABA/ABA/ABAA

Now comes the repetition. The first line in the poem is used as the last line in verse two and four, as well as being the third line in verse six.

Meanwhile the third line from the poem is used as the final line in verses three and five, as well as the final line for the poem, line four verse six.

It’s important to remember that in the final verse – the first, third and fourth lines have to rhyme. It can therefore be easier to start with the conclusion (the final verse) when writing.

Hopefully the inspiration of different forms of poetry will help you find a new way to express your music, but don’t forget to play around with the formats, maybe even combine some techniques and expand on others. Or simply use it to practice songwriting. Either way, just have some fun.