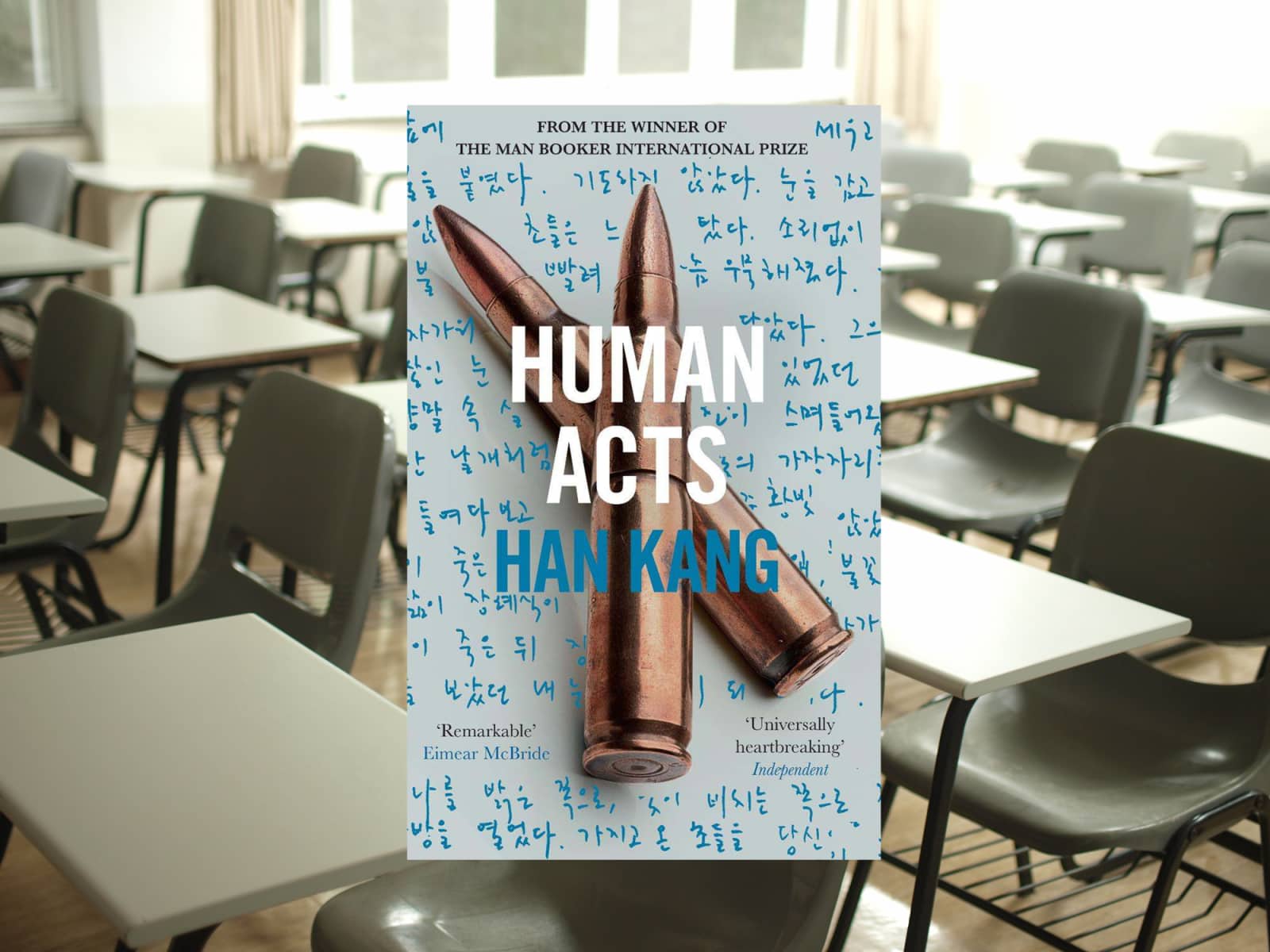

How do you tell a story that’s as true as it is heart shattering? Human Acts reveals the personal tales of the Gwangju uprising in 1980 South Korea, where workers, students and kids spoke against a military regime that oppressed – and would be responsible for the mass murder, torture and censorship of it all. The characters in the story are fictional, but they represent those that lived in these times and died in them as well.

Han’s work looks at; the kindness of humans against a backdrop of savagery; incomparable loss and grief; the breaking of spirits; the age-old question of just what is a spirit? A soul? And what are the acts that define and separate us – dividing the victims from the killers?

The book’s introduction provides the political backdrop, and it’s worth reading before diving straight in. For though the book expands on the context of the times with working rights, mistreatment, censorship, and the atmosphere of oppression, it’s not the focus of the book – that’s in the horror of those who fought for a better future. From Dong-ho, a young boy of fifteen, who’s searching for his friend in rooms filled with never-ending corpses, to the spirit of one who died, and later to survivors of the uprising, though ‘survival’ and what defines us is questioned throughout.

In sharp contrast the book opens up on the tranquilness of nature, its place juxtaposed by the number of dead that lay waiting to be identified or still to be released. It feels at points as though nature is a metaphor for the grieving, for the never-ending pressure of those living in these hard times, and in trying to survive; ‘those trees over there, who hold those long breaths within themselves with such unwavering patience, are bending under the onslaught of the rain.’

Time in the book flickers like the candles for the dead with jumbled memories shooting forward in a flash, or to slowly grow into a steady picture, while the characters that form the six dividing chapters of Human Acts(excluding the epilogue) have their past move to times before, during and after the uprising. Just as their present day tries to move around them. Overall, however, the chapters are in chronological order and provide multiple perspectives, along with the outcomes of those involved. The link that connects them, apart from hope, fear, sadness and hurt, is – Dong-ho. The events in Dong-ho’s life continuing past where the first chapter left, and ending with the infliction the uprising brought to his family – to his mother who tells her story last.

In the chapters of those who survived the onslaught, their damaged bodies shown to still linger with life, is a spirit that’s unable to move on as it lies stuck within the past – within the uprising. Their stories never fully concluded and so you never know if they are able to move forward, but you suspect not. Han’s decision not to give them an ending leaves the reader to wonder if the traumas of the past will overcome them, as it has for others mentioned in the book – with suicide sought to escape it. Thus the crimes carried out by the government in Gwangju are still causing a growing list of victims.

The bodies of those murdered in the book are often talked about without emotion, and Han instead lists the grotesque acts of violence carried out on them – allowing you to make your own mind up about the perpetrators. But the bloating body in the corner, turning black and putrid, no longer has a mind to be used. The damage inflicted on their body going beyond mere silencing, and when described against their only identifiable feature – the clothing – ‘the pleated skirt with its pattern of water droplets’ you’re reminded that a soul was there, vibrant, young and innocent. There are so many dead bodies that the lead character, Dong-ho, keeps a ledger full of their details, his eyes searching for his friend amongst them. But is it more than this, is he atoning for a trauma too hard to face?

Initially in reading the book it’s hard to find an empathetic link to Dong-ho’s friend – often because he’s mentioned as just that. It’s only later when Dong-ho describes his friend by his attributes and idiosyncrasies, that a connection is built, and an immediate urgency is created for them, the empathy consuming.

CENSORSHIP Censorship censorship – the dead not even to be mourned, the lives taken not to be spoken off, and the memories left to be unshared. This is seen in many ways throughout the book, and though there is a specific chapter highlighting the censorship, and the defiance of those who spoke out act against it, its feel more effective and gut-punching in the second chapter – where one of those who were killed, talks about their body being stolen, hidden, buried and burned away.

The writing in Human Acts is highly thought-out, its staging and narratives as important as the chosen words;

‘…surrounded by bodies gradually breaking down into their constituent parts, I was alone among strangers.

There was worse to come.’

This break in paragraphs being an example of Han’s placement of lines to emphasise previous points, while raising the tension of what’s to follow. It works like a bucket of water thrown to the face – waking you from having succumbed to the horrors already presented.

Human Acts is a beautiful portfolio of Han’s writing, especially the apparent ease in which she switches narratives. Starting initially from second person; placing the reader as a young child caught in grief and regret, to later chapters where survivors direct their testimonies to you, or to themselves. This second person narrative reads at times like a set of stage directions – a voice in your head telling you what you see, hear and act ‘…you don’t know what happened after that. You were too busy crawling, trembling, into the next street, a street where a sight even further from your experience was unfolding.’ The reader becoming a part of the history that’s about to be told.

Han’s writing moves between first, second and third person narrations depending on the character’s tone, and directing as such the reaction of the reader. Han’s use of the first person narratives guides the viewer to their emotions; creating a greater sense of empathy for the pain of a lost soul, while for a survivor of torture it produces feelings of anger. The epilogue is also written in the first person as Han describes her own personal relationship to Gwangju, her concerns and her findings – leaving you to feel much of the same.

In Human Acts, Han has immaculately preserved the past, while providing a worrying voice about the future. The acts of humans never being far removed, whether it was from Gwangju, Vietnam, or the tenants killed in 2009 over desirable land in central Seoul. While in the replay of the Gwangju uprising, you’re shown scenes similar to a battlefield, but strikingly the victims didn’t even know they were going to war.

The third person narrative adds to the strange sensation of a girl trying to remove herself from the physical pain and its memory, while in the character of the mother, Han does the astounding, and conquers the complex situation of switching between first and second narration, making it seem natural – like the bond between mother and son; ‘My Dong-ho, I was thirty when I had you. My last-born.’ These changes in narration are particular effective in the first two chapters – where the shared memories of two boys are reflected on like an open dialogue, with both sides being shown.

In this sad story of a nation’s time, Han has carefully and tenderly created an epitaph to the lives taken, to the spirits forever changed, and to the hurt that lingers and lasts. Human Acts is a faultless piece of work that calls us to notice our news and the history of the world, but it also shouts out the acts we’re capable of, our essence of being alive, and of being human.

Other Notable Works by Han Kang:

- The Fruit of My Woman 2016

Book Edition Information:

Publisher: Portobello Books

ISBN: 9781846275975

Cover Design: Tina Fields

Presented Edition: 2016 Paperback

Background image courtesy of MChe Lee on Unsplash