b.1856 – d.1925

There’s a story to be found behind a pretty picture. Find out how Singer Sargent came to do some of his most famous pieces, to the reception they received.

John Singer Sargent may seem like a traditional artist; his portraits were often commissioned, while his work held a symmetry of grandeur to it. But, he was also experimental, moving across various styles of art that showcased his versatility. His paintings traversing the movements of realism, impressionism and an appreciation of the Pre-Raphaelites, although it’s John Singer Sargent realistic portraits that are most known and well cited.

In the past, Sargent’s work has been criticised for being too posed and polished, followed with an interpretation that it shows a lack of imagination. However, in ‘Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose’ (1885-86) the scene was not one of real-life, but was a collections of inspirations, the first being inspired by a boat ride in the countryside of England. Then, as many artists do Sargent started to formulate an image in his head, from the exact look of his models – changing them even to fit – to the surroundings, light and flowers; using lanterns and lilies inspired by the popularity of Japanese art in the mid 18th to early 19th century. He was also particular in the demands he placed upon his artwork, for example in creating Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose he would only paint when the light was absolutely right – even when that meant just a few minutes towards the end of each day, his hands quickly working to record the dying light. And yet he was his harshly critical of his work, often undoing the last brush strokes till it was just how he wanted. This commitment carries through into the final painting; the light perfectly showing the transition of night to day, when both are in existence and the lanterns begin to glow – their change captured in the girls’ faces as they look inward, spellbound by it all.

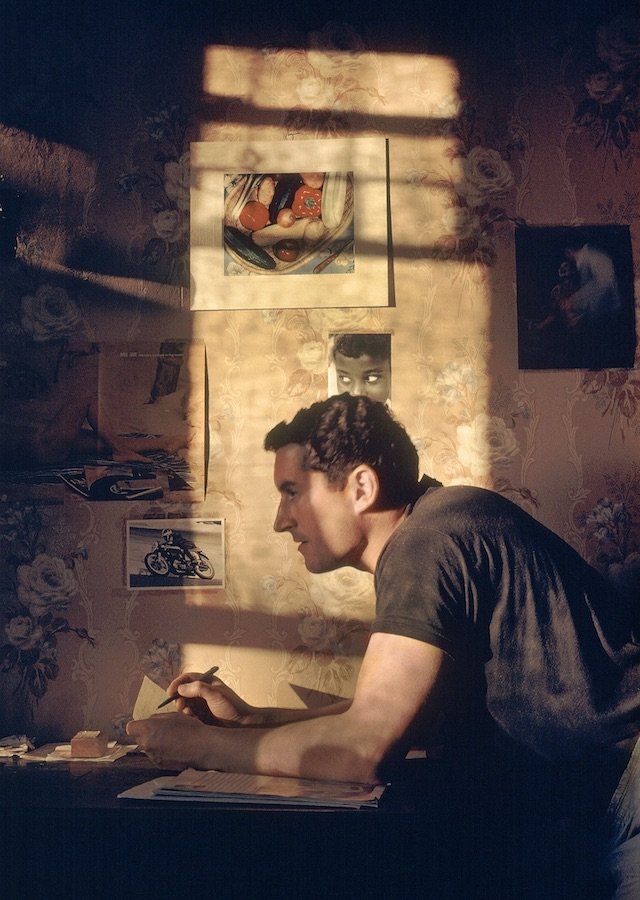

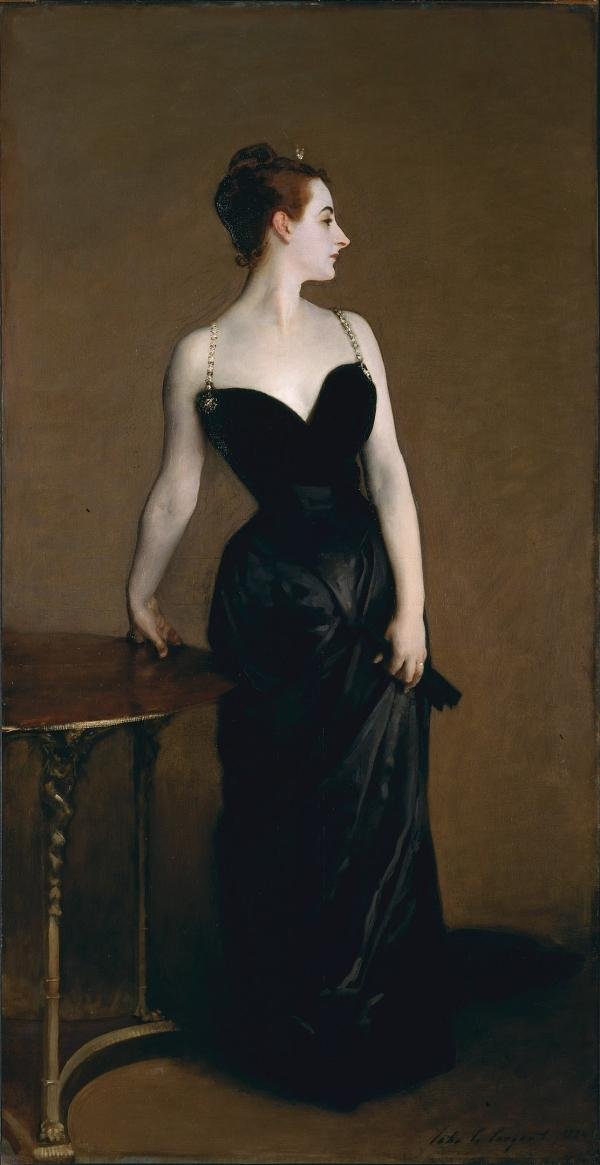

Madam X (1883-84)

Madam X (1883-84)

Sargent’s paintings create a sense of being pulled into the middle of a story; the scene is set, the models framed with expressive moments of drama, even the use of light is suggestive in its meaning. In Madame X (1883-84) for example there’s a story of allure, strength and the untouchable. Finding instant fame, the piece also received a fair amount of disparaging remarks both for the artist and its model; due at the time to the scandalous style of the portrait – the exposed nakedness of her skin, the slipped shoulder-strap (later repainted un-slipped) the black corseted outfit, even for her body language which is both strong and feminine. The painting was new and exciting, Sargent’s technique flawless whilst capturing a sense of independence; a woman trying to make her own mark in society, even if at that time the painting was to her detriment.

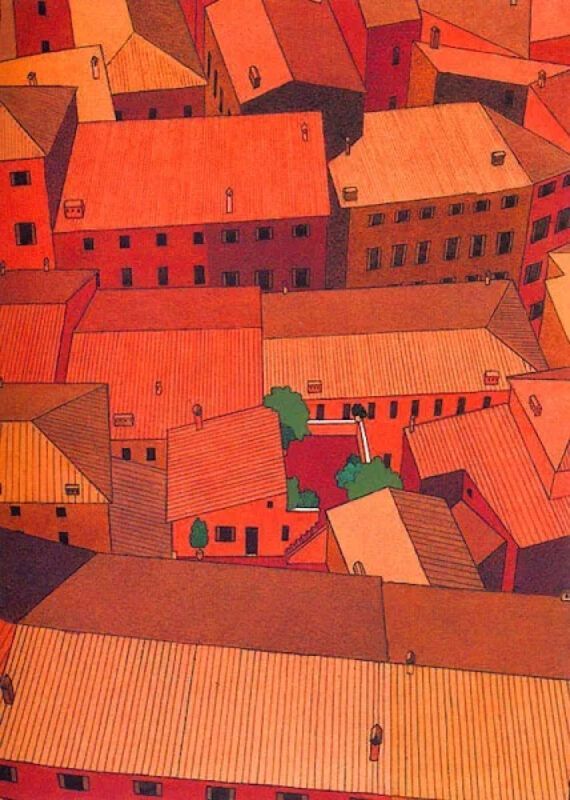

Despite these captivating paintings, each holding a layering of stories, the works he created in Venice such as Venetian Onion Seller (1880-82) and Venetian Wineshop (1898) hold a greater depth of realism with an everyday atmosphere that’s far more intimate. Reflecting a society of the masses that’s away from the high-end commissions.

Venetian Wineshop, 1898

Venetian Wineshop, 1898

Eclectic in themes and styles Sargent produced a vast body of work covering portraits, landscapes, society and architecture, predominantly in oils and watercolours (especially the latter), but the strings that hold Sargent’s work together is his relentless pursuit of beauty – settling for nothing less.