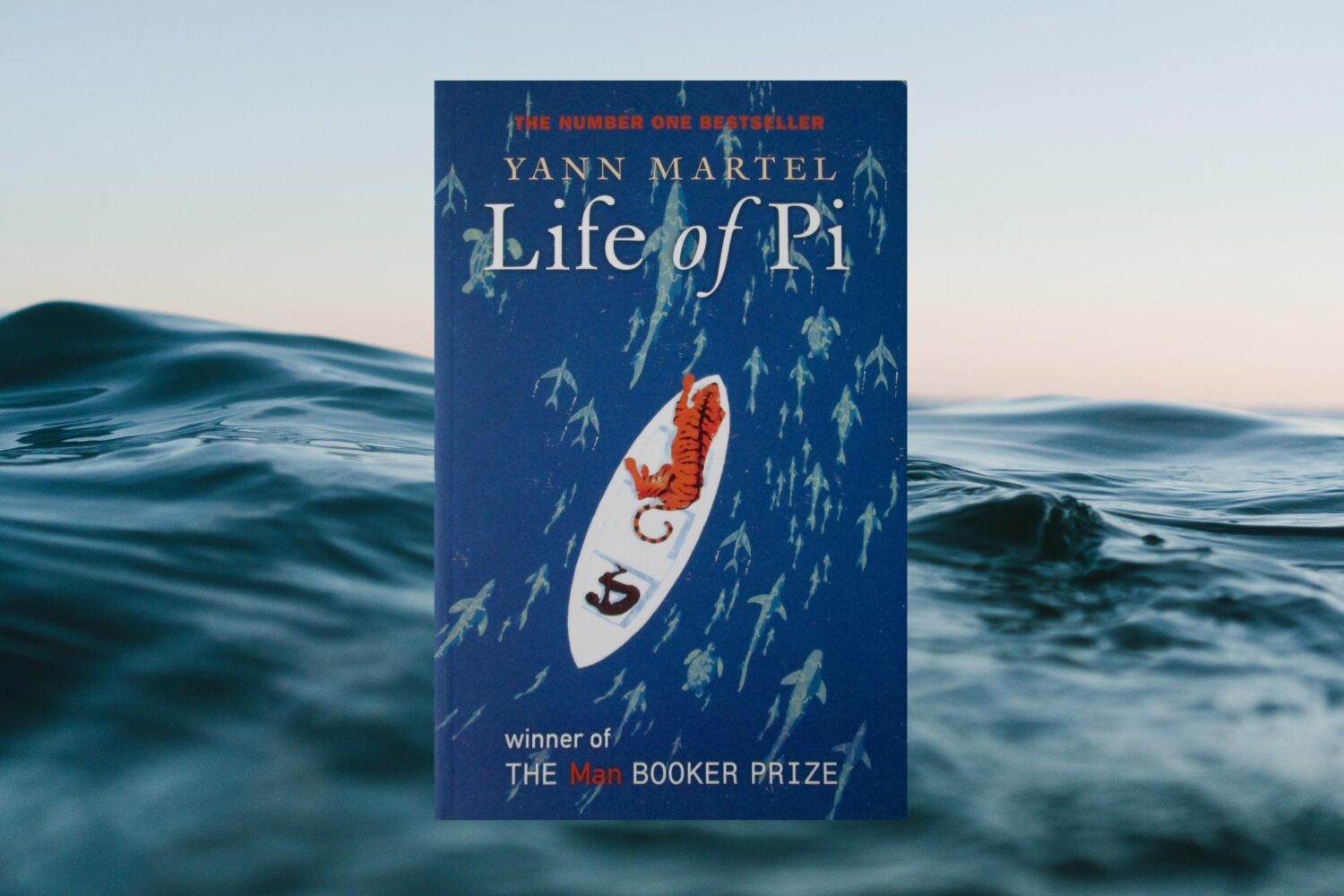

Pi, short for Piscine, is smart, resourceful, and has ‘nothing but the fondest memories of growing up in a zoo’ – his father having owned one. Philosophical, spiritual and full of adventure, Pi carves his own identity very early on. The first part of the book following him into late adolescence; his continual love and fascination of animals, along with his different religious faiths – which he practises together – defying the rules in being told to just choose one. He’s also someone not to be beaten down by life, or by bullies, taking the opportunity to address the teasing of his name – which is purposefully mispronounced as pissing – by writing the mathematical abbreviation of Pi 3.14 on the blackboard at the start of every lesson, until it has at last taken hold, for ‘repetition is important in the training not only of animals but also of humans.’ This initiative in taking charge and changing the narrative is something Pi does again later on in the book both in living, and in retelling, the horrible tragedies that occurred on his family’s trip from India to Canada, and which left him stranded in the Pacific Ocean with various animals from the zoo. That is until it becomes slowly whittled down to just him and an adult Bengal tiger.

Full disclosure, there were certain pages involving a zebra that I initially skimmed (although I went back to them later), but at the time I could see its trajectory, and well, didn’t want to know the details. Suffice to say if you have cried to…well, basically any film by Disney, this is going to hit you hard!! But, on the other hand, if you’ve ever watched Watership Down and have come out the other side as a sane individual, it doesn’t matter, this book will still destroy you. And yet it’s one of the best reads you’ll experience in your lifetime. Now I may have made it sound gut-wrenchingly depressing, it still is, but that’s only a part of the book, and you can’t have a fall without getting back up, and so with this larger than life tumble you can only imagine our hero Pi will come out roaring – and so to speak he does.

In starting with the author’s note, Yann Martel explains a random case of meeting a passing stranger, who after mentioning just a brief part of Pi’s story, suggests a meeting between the two – although this fictional it plants the seed of possibility within the reader. From this Martel then meets Pi who recites his story and the rest of the book in the first-person narrative – although Martel’s voice mingles in-between as he comments on current day Pi, including both how he feels, and what he perceives Pi as feeling. These interjections work as though Martel is merely a listener to Pi’s life, and is there just to write his story, creating a sense of the reader’s voice being included in the book as we too look on astounded, sad or in wonder at the story, while having the added benefit of commenting on Pi both in a personal and yet removed tone.

Together the two unfold Pi’s unlikely, but lived-in story, and like the insurance board who later investigates Pi’s survival at sea – which is read like the dialogue of a play, increasing intensity and removing distraction – you’re left with a choice in how you wish to perceive his tale, one which changes the narrative. In this, and in many ways, Yann Martel has created something truly unique – no wonder it’s been such a lasting success.

Another area of the book is Pi’s ability to never be one thing, he has multiple points of view, blends faiths, and adds factual knowledge of the world – which forms the first part of the book. His character developing to become the sixteen-year-old boy who will one day become stranded at sea. Pi’s different viewpoints on life are his salvation, and a strong pull to the reader in wanting to follow his journey.

One great tragedy after another, Pi is left with just a single choice, to rise to the adversity that faces him, or put simply; die. He chooses the former, the audience brought into each of his successes and failures as he learns to survive in a lifeboat stranded in the middle of the ocean for months at a time, and with the additional threat of a tiger. But as I’ve mentioned Pi is clever; he learns how to fish, how to keep the boredom away (and save his mind from insanity), while all the while worrying when will the tiger attack? So initially Pi comes up with plans on how to get rid of him; ‘Plan Number Three: Attack Him with All Available Weaponry. Ludicrous. I wasn’t Tarzan. I was a puny, feeble, vegetarian life form’. The book is strangely humorous for all its parts, while telling a story of bravery, with Pi choosing to live with a tiger on the boat and using his childhood knowledge to train the naturally-instinctive wild animal, and form an unstable hierarchy in which he, the puny human, is the dominate alpha.

At least this is the story on the surface, below that is what people do to survive, how someone can change when faced with extreme adversity, and what it means to have humanity, to have a soul – one which defines who we are.

Throughout the book there’s a surrounding sense of hope, even when the scenes seem more than despairing, while in Pi’s story of survival we’re given moments of magic, and a companionship of sorts between Pi and, ermm, the tiger??! And eventually leading to a land too strange and bewildering to have actually existed – being a part of the book’s charm; creating questions; embracing surrealism; and having an endearing tone – as you feel for Pi and all of his choices and perspectives. Leaving you with a sort of wry smile to your face, a marvelling at humanity’s need to survive and of Pi’s personal triumph in still retaining a sense of who he was/is – and which is stronger than anything that may try to attack, or eat away at him.

Book Edition Information:

Publisher: Canongate

ISBN: 978-1-84195-392-2

Cover Illustration: Andy Bridge

Presented Edition: 2003 Paperback

Background image courtesy of Matt Hardy on Unsplash