Michael Mapes’ art is like watching a curator as they begin gathering a range of objects for exhibition. At first you’re intrigued as to what the connection is, and then there’s the big reveal – when you see the whole show and it’s both engrossing and insightful.

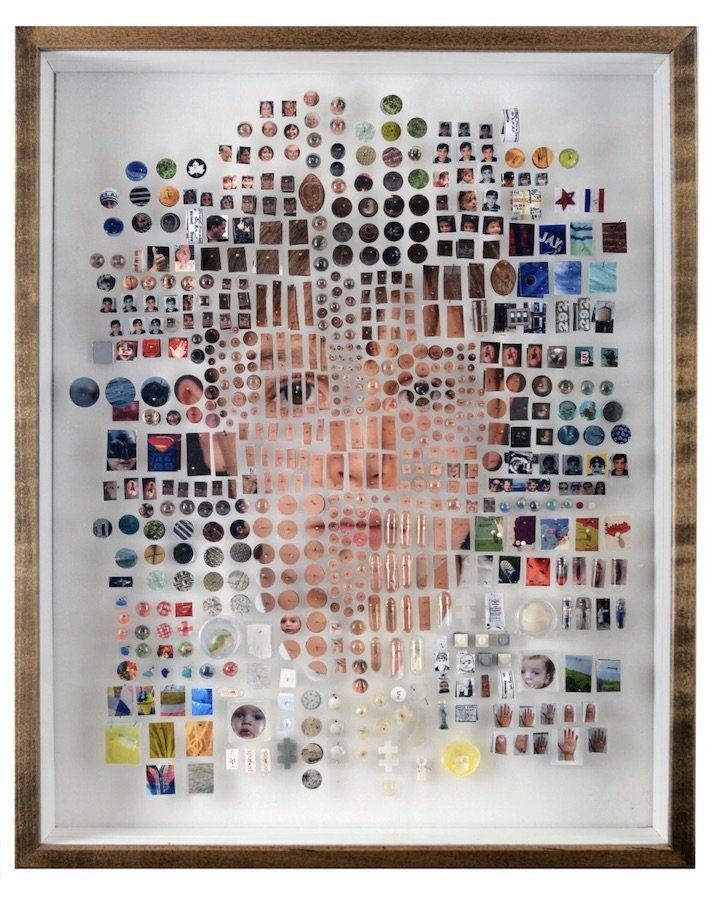

His portraits varying from modern-day photographs, pin ups, to Dutch paintings of the 16-17th Century. What makes them so distinctive is how they are made; from a build-up of minute objects and images. The items ranging from “biographical DNA” – fingernails, dental records, hair, and eyelashes. To man-made – magnifying boxes, glass eyeballs and jewellery. Along with the natural – seashells and roses. Not forgetting images; tiny photographs, prints of the human body and family stills.

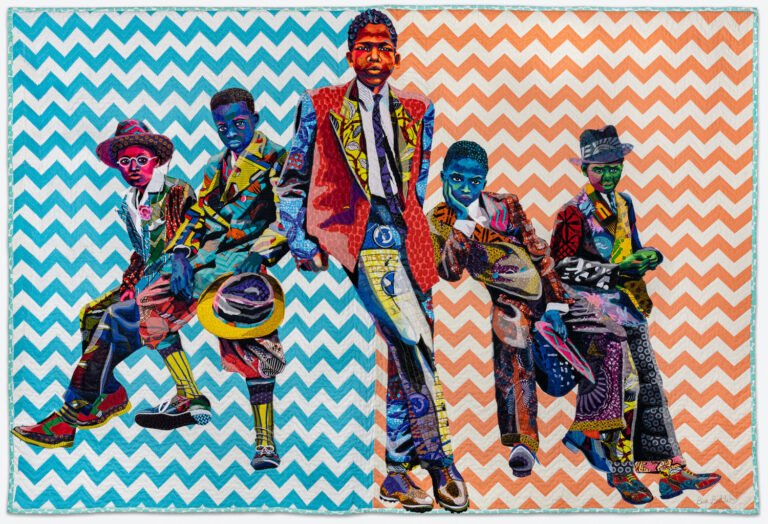

Specimen 480: Roxanne, 2015. Series: Pin Ups. Michael Mapes.

Specimen 480: Roxanne, 2015. Series: Pin Ups. Michael Mapes.

When reconstructing an image Mapes also includes the original artwork, but in a deconstructed and then reassembled form, to allow for more wide-ranging items to be included – the end result being a biological breakdown of the subject. In Pin Ups Mapes has used over-arching pin-up illustrations from the 20th century, creating the model from cosmetics, a cigarette, fake nails, rose thorns, nude female photographs and close-ups of the female anatomy then circled in black – maybe a dark hint at the over-sexualising of the female form?

These objects are held in place, as in all of Mapes’ work, by having pins pushed through their centres much like the entomology of Victorian days, where science exploded as being the rationale for everything. Its rigorous and somewhat mechanical methods are used to dissect humans down to their basic biology, and in Mapes’ work he gets us to do this in extension with society; how we take basic information, over-analyse it and from this form an opinion. His work asking us to question our own deductions of so called scientific information.

Between the pinned objects of his portraits, Mapes leaves gaps big enough in part for the analyses of the individual objects and their study in relation to the image as a whole, but it can also be telling of what you don’t see; that not everything can be tangible in a person.

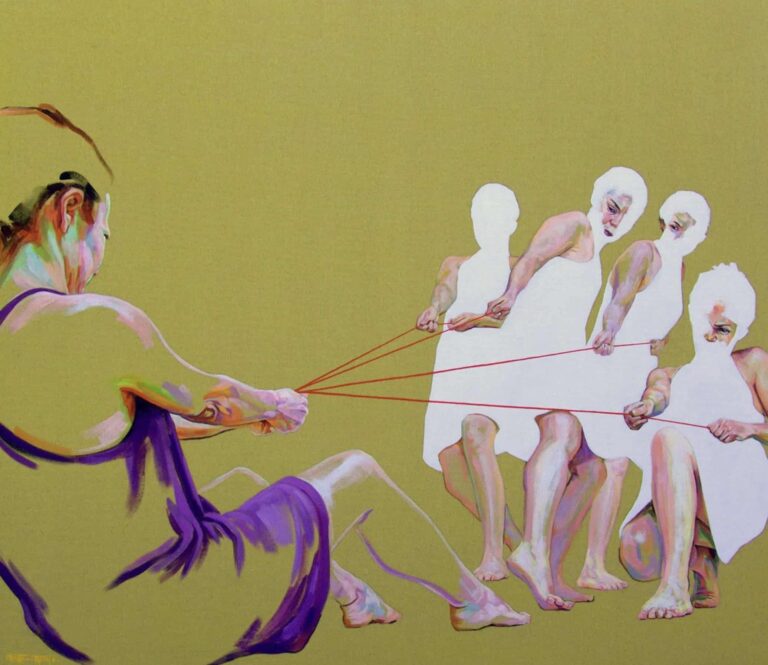

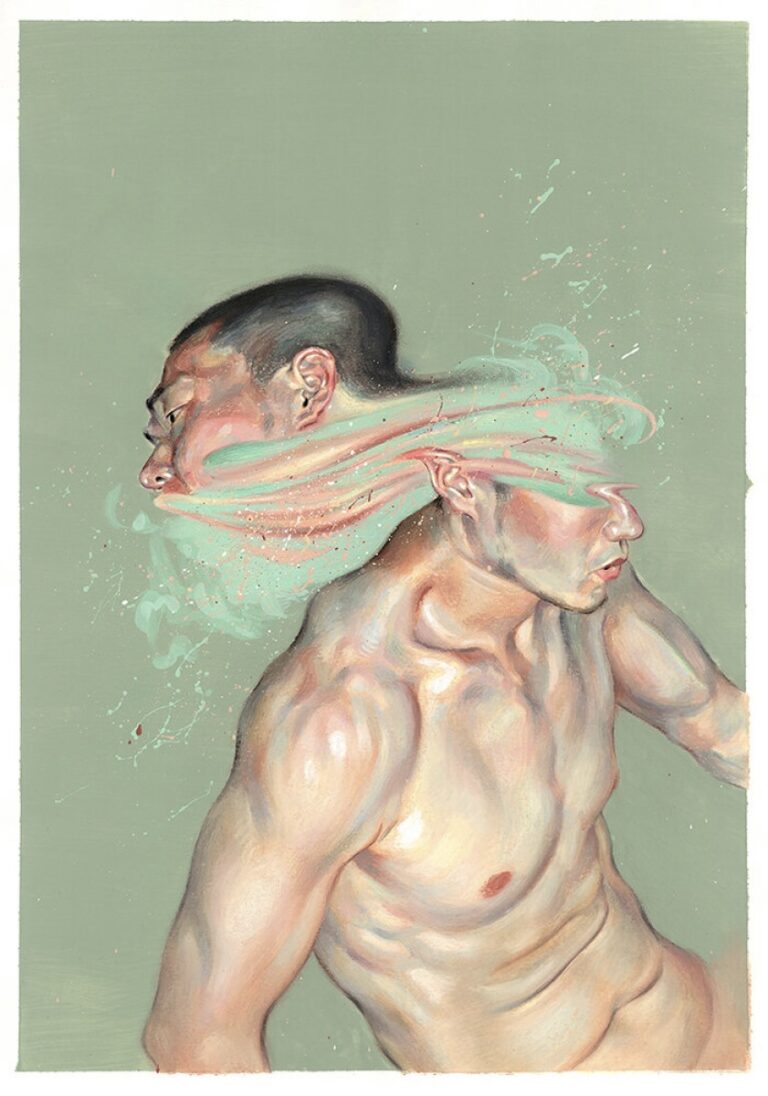

Specimen v 07, 2017. Species: Vanitas Specimen. Michael Mapes.

Specimen v 07, 2017. Species: Vanitas Specimen. Michael Mapes.

We recently contacted Michael Mapes, who very kindly answered some questions we had about his work.

You reconstruct portraits through a scientific display using in part “biographical DNA” and man-made objects. What do you think of today’s technological advances in shaping a person’s portrait, such as data sharing and social media?

This question has inspired me to consider the advances since coining the term “biographical DNA” so many years ago. My historical practice of garnering content is more referenced to biological – hair, x-rays, baby teeth – than behavioral. While I used to think of digital footprints as more ephemeral, they now seem more likely to survive than their analog counterparts, though in my biased estimation, less interesting to look at.

How did you first come to explore such themes of dissection and reconstruction in your artwork?

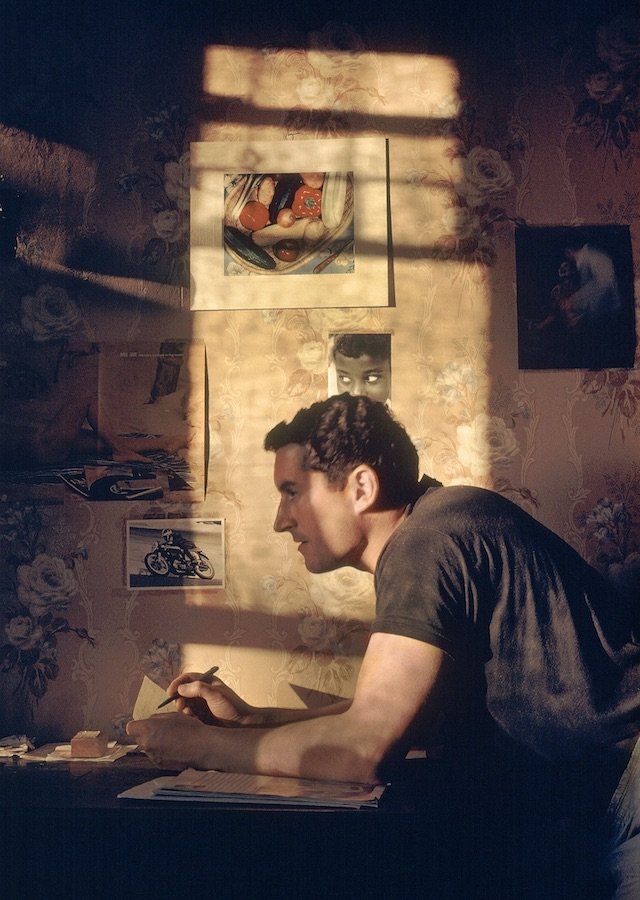

The metaphor was initially generated through studio exploration – hole punching a small photograph and using sewing pins, on hand, to reconstruct it. I saw the metaphorical potential, as it combined entomology with artistic compositional references. The metaphor remains interesting to me as I broaden the lens by pushing the references.

What inspires your choice of portraits? And have you created any artworks that have a degree of self-portraiture to them?

The choice of subjects in my works varies as you might suspect. Initially, I chose the subjects purely based on various degrees of personal connection. Willing subjects, for both photography and collection of content. The Dutch Master series was inspired by my response to increasing interest in celebrity subjects – and my reluctance to oblige. The celebrity of the iconic paintings of the Masters turned out to be a good creative instinct.

As for self-portraiture in any degree, I exist in very, very subtle ways in many works. Not as much by design as necessity (and creative license), though the significance isn’t lost on me. A fingerprint there, a dental x-ray here. I did portraits of my parents a couple of years back that have inspired me to give more consideration to a work of myself. Who knows.